The Cannabis plant is teaming with biologically active natural products, known as “phytocannabinoids” or simply “cannabinoids.” More than 100 of these chemicals have been identified, and several are under investigation as potential treatments for a variety of ailments including chronic pain, neurological disorders, cancer, and inflammation.1

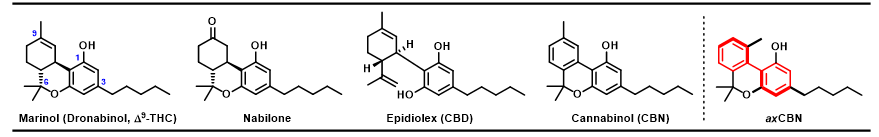

Currently, there are only four FDA-approved cannabinoid drugs: Dronabinol, used to stimulate appetite (particularly useful for patients with AIDS-related weight loss), Nabilone, an antiemetic (used to treat nausea and vomiting in patients receiving chemotherapy), Epidiolex, a treatment for rare forms of epilepsy known as Lennox-Gastaut syndrome and Dravet syndrome, and Nabiximols, used to treat neuropathic pain related to multiple sclerosis. Nabilone is undergoing additional studies to determine if it can be used for the treatment of chronic pain, fibromyalgia, ulcerative colitis, and multiple sclerosis.2–5

As potential analgesics (pain relievers), cannabinoids are receiving special attention due to the ongoing opioid epidemic. But while Cannabis has a long history of medicinal use, its efficacy and long-term effects has not been rigorously established.1,6

Despite recent advances in cannabinoid research, most efforts have focused exclusively on Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) and cannabidiol (CBD), leaving others, like cannabinol (CBN), underexplored. Unlike THC, CBN is not a scheduled drug—it’s only weakly psychoactive and considered nonintoxicating.8,9

THC has been the subject of numerous structure-activity relationship (SAR) studies—systematic investigation of the relationship between the molecule’s structural features and its biological activity—which have indicated that the C-3 side chain and the C-1 hydroxy (OH) group are major contributors to its affinity for the cannabinoid receptor types 1 and 2 (CB1 and CB2, the primary biological targets of cannabinoids). Furthermore, structural elements at C-9 and C-6 may also contribute to the observed bioactivity.10,11

It is well understood that THC is much more pharmacologically active than its cousin, CBN. This is likely due to the relative planarity, or “flatness,” of CBN compared to THC, a distinctly three-dimensional scaffold (3D features indicated by wedged and dashed bonds). Why is three-dimensionality important?

If we consider the basic “lock and key” model of protein receptors and ligands (enzymes, drugs, etc.), two key concepts emerge: first, a good lock is intricately shaped to be opened only by select, carefully matched keys. Second, a good key is one that is well-matched to its intended lock, and not well-matched to other, unintended locks. What can make a key undesirably versatile? Among other things, a lack of unique structural features, like a specific three-dimensional shape!

Is it possible to redesign the (relatively) 2D CBN so that it’s more 3D like THC?

Yes! The Grenning lab perceived an unrealized potential for the CBN framework: axial chirality. Axial chirality is a property that gives molecules three-dimensionality about an axis (indicated by bolded bonds), rather than an atom (or “point”). Like THC, axially chiral CBN, “axCBNs,” would be distinctly three-dimensional (about an axis, rather than a point), but the biaryl core of axCBNs (highlighted in red) would allow for simpler manipulations of the structure, thus better facilitating SAR.

A concise, scalable synthesis of axCBN was developed by a Grenning lab alum, Dr. Primali Navaratne, and the compound was submitted to collaborators for evaluation of its bioactivity. In a rodent model of neuropathic pain, axCBN reversed pain-related behaviors in a dose-dependent fashion (drug effects should be predictable based on dose for both safety and efficacy), and was shown to produce less intense cannabimimetic effects, the behaviors associated with Cannabis intoxication, than THC. More importantly, the dose of axCBN required for symptom relief was about two-fold lower than the dose that produced cannabimimetic effects.12 (Read the full axCBN story here!)

This encouraging preliminary data inspired us to continue exploring axial chirality in cannabinoids. To do this, we set out to design and optimize a second-generation synthetic route to these molecules, and this endeavor has been the focus of my graduate research. More details to come in my next research post, so stay tuned!

REFERENCES

(1) Reekie, T.; Scott, M.; Kassiou, M. Nat. Rev. Chem. 2018, 2, 1-12.

(2) De Vries, M. et al. Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 2014, 1525–1534.

(3) FDA Approves First Drug Comprised of an Active Ingredient Derived from Marijuana to Treat Rare, Severe Forms of Epilepsy | FDA, 2018.

(4) Wissel, J. et. al. J. Neurol. 2006, 253, 1337–1341.

(5) Nielsen, S.et. al. Curr. Neurol. and Neurosci. Rep. 2018, 1–12.

(6) Elikottil, J.; Gupta, P.; Gupta, K. J. Opioid. Manag. 2010, 5, 341–57.

(7) Golombek, P.; Müller, M.; Barthlott, I.; Sproll, C.; Lachenmeier, D. W. Toxics. 2020, 41.

(8) Petitet, F.et. al. Life Sci. 1998, 63, 1-6.

(9) Mahadevan, A. J. Med. Chem. 2000, 43, 3778–3785.

(10) Prandi, C.; Blangetti, M.; Namdar, D.; Koltai, H. Molecules. 2018. 23, 1526.

(11) Bow, E. W.; Rimoldi, J. M. Perspect. Medicin. Chem. 2016, 8, 17–39.

(12) Navaratne, P. V. et. Al. ChemMedChem 2020, 15, 728–732.

2 responses to “Cannabis-Inspired Drug Discovery”

Good morning,

Greetings,

You can also check Chromenopyrazoles. Not explored much in the area of cannabis related drug discovery.

Thanks and Regards

Vishal Agarwal

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Vishal! Thanks for commenting and sharing your insight. I’m always interested in new ideas!

LikeLike